HAS RELOCATED TO

Robert Wexelblatt

“Hsi-wei at the Moon Festival”

That summer Chen Hsi-wei traveled through the Emperor’s westernmost province, Liangzhou. It had been seven years since the peasant/poet left Daxing to become a vagabond, selling his straw sandals and leaving behind those verses that would eventually win him a measure of fame. He was still in his twenties; it would be years before he would receive invitations to stay in the villas of high officials and to banquets by cultured wives eager to show him off to their friends. Back then, Hsi-wei found shelter in the towns as he did on the road, whatever he could afford. He looked out especially for rundown inns. If the place had a stable he could usually stay in it for hardly any money, sometimes for just a pair or two of straw sandals. If the weather was good, he could sleep out of doors; but when it was not he would talk his way into barns, storerooms, pantries, and, on one occasion, a closet.

On the fifteenth of Osmanthus, shortly before noon, Hsi-wei passed through the Yicheng’s North Gate. Though it was the day of the Moon Festival, few people were on the streets. All day, rain had been pouring down from a gloomy, sunless sky, and it was unseasonably cold as well. Hsi-wei arrived in the town drenched and shivering.

Not far from the gate he spotted an inn that still showed traces of red paint on its gray boards. Behind it was a small stable, which looked on the point of falling-down. Hsi-wei went inside the inn hoping to warm himself but the main room felt damp and chilly. However, at the far end, under a hole in the ceiling, the landlord had set up a brazier. The locals had pulled stools up in a tight circle around the fire where they drank and gossiped. Nobody looked at the dripping stranger trembling with cold.

Hsi-wei noticed a doorway and peered inside. A heavy-set man with an ugly mustache over his lips and a cleaver in his hand stood at a high table cutting up pork, cabbages, and spring onions. A basket of eggs rested next to a big pot of water on the table. Hsi-wei had heard that the local specialty was boiled pork prepared with a coating of egg white.

The innkeeper gave Hsi-wei a contemptuous glance and said, “You look like a half-drowned puppy.”

“I would like to stay here tonight.”

The man pointed up with his cleaver. “I have two good rooms up there. Clean ones. You don’t look like you’ve got enough money for either of them.”

“Most likely not, but I would be grateful if you would permit me a corner in your stable. I can pay with some good straw sandals.”

“So, you’re a sandal-maker? Well, it’s late in the year for straw sandals and I don’t need any, but I’ll let you stay if you make a pair for my wife and one more her mother. Both small.”

Hsi-wei gave a short bow. “That is agreeable. Thank you.”

The landlord grunted. “It’s settled. Now, go in with the others before you start sneezing all over me and this pork.”

In the main room, there was still no place by the fire. Just then Hsi-wei heard the sound of a horse’s hoofs outside. A minute later, the door swung open and a tall man in a dripping official’s gown came in, shaking out a soaked fur cap. He was distinguished looking, spare, about forty with an intelligent face and keen eyes. The men around the brazier looked over at him with something like apprehension. The man ignored their gaze and called for the innkeeper.

Seeing the official’s gown, the landlord adopted a deferential manner.

“What can I get for you, Sir? Wine? Perhaps you want a room?”

“First, you can see that my horse is stabled and brushed dry,” said the official.

“Yes, Sir. I’ll send the boy at once.”

Hsi-wei was still shivering by the door, right next to the newcomer who turned toward him and smiled.

“We’re both in the same state,” he said, then nodded toward the circle of men around the brazier. “It’s cold here but it looks warm enough over there.”

“They won’t make room by the fire.”

The official grinned. “I believe I can fix that. Look, whatever happens, just stay where you are.” Then he summoned the landlord again.

“What have you got to eat?” he demanded.

“I’ve been preparing our good Liang pork, Your Honor. There’s some ready now.”

“Excellent. Please put the meal in a bowl and take it out to my horse.”

“What? To your horse?”

The official took out a purse and shook it so the innkeeper could hear the sound.

“Yes, take it to my horse and do it as quickly as possible. We’ve been on the road this whole wet morning and the poor beast’s famished.”

The men around the fire paid close attention to this astonishing exchange. Their mouths fell open.

The landlord scratched his head, looked at the purse, shrugged, and vanished into the kitchen. A few minutes later, he came out with a large clay bowl and headed out the door.

All the men around the fire got up and followed. They’d never seen a horse that ate Liang pork.

As soon as they were gone, the official sat down on one of the stools closest to the brazier and motioned for Hsi-wei to sit beside him.

The man stretched his hands toward the heat. “Now, that’s better.”

A minute later, the innkeeper came back with the bowl and followed by the locals.

“Your horse wouldn’t touch the pork,” the innkeeper complained.

“Well, that’s a pity. But never mind. Just put the pork by the fire here. It will make a good meal for me and my friend. . .” The official looked at the poet and raised his eyebrows.

“Chen Hsi-wei. Sandal-maker. At your service.”

The official nodded in a way that was friendly rather than imperious. “Wang Jiang-guo, Assistant Magistrate of Meishan. Will you join me in the meal?”

“Gladly,” said Hsi-wei. “Clever way to get these warm stools and generous to share your horse’s feast with me.”

Wang gave Hsi-wei an avuncular smile. “The brotherhood of distress.”

The locals filed out, grumbling.

As it happened, Hsi-wei and Assistant Magistrate Wang had a good deal to say to one another. Though the conversation began tediously with comments on the deplorable condition of the roads and the nastiness of the weather, they soon moved on to more serious subjects such as the progress of Emperor Wen’s land reform and the plan for distributing his new coins. Wang spoke of the number of new temples he had seen on the way from Meishan, which led to a discussion of the Emperor’s support for Buddhism. Though neither was a Buddhist, both judged the policy a good thing, on the whole.

“So long as he doesn’t neglect the sound teachings of Kong Qiu, of course,” Wang said.

“Will you be staying long in Yicheng?” Hsi-wei asked.

“No, not long. I’m just here to collect a report on some dubious relatives of one of our big landowners in Meishan. The fellow is at the center of a complicated case having to do with the improper acquisition of land and evasion of the new laws. The man’s in-laws are from Yicheng and it appears his wife’s uncles are involved in the scheme.”

Hsi-wei was surprised that someone like Wang would be given such a task. “All the way from Meishan just to collect a report?”

“Yes.”

“But, with respect, wouldn’t that be a job for somebody of lesser rank?”

Wang nodded. “Normally, yes. But the matter is urgent and no one at the magistracy wanted to be away from home during the Moon Festival. As it doesn’t matter to me, I volunteered.”

Hsi-wei noted the melancholy in Wang’s voice. Either his new friend had no family or he had one from which he wished to escape. Hsi-wei thought the former more likely.

“Tell me about yourself, young man,” Wang asked. “How did you come to be an itinerant sandal-maker?”

“When I was a boy, my uncle taught me how to make sandals.”

“Look, we’re both here on our own on the day of the Moon Festival. The day’s dreary but it’s still a festival. I like your company and we probably won’t see each other again after today. Let’s talk like new friends who pretend to be old ones. So, come now, I’m sure there’s more to your story.”

“It’s a story that’s hard to believe.”

“Well, that’s intriguing. Let’s hear it.”

Hsi-wei told about being sent to the capital as a boy because the government put out a request for illiterate peasant boys with fast-growing hair; how he was chosen to take a message to General Fu in the South; how he was chosen, his head shaved and the words written on his scalp; how, after his hair had grown back, he was sent on his dangerous journey. Later, he learned that the message was from Yang Jiang himself and proved critical to the victory over the Southern dynasty that enabled him to declare himself Emperor Wen of Sui and unite the Empire for the first time in three hundred years. He told Wang that on his return he had been offered the customary rewards but asked instead to be educated because of having words he couldn’t read on his head. He described the strict Master Shen Kuo, compelled against his will to teach a peasant lad; how he had been beaten by Shen and mocked by most of his well-born classmates, but also found among them some good friends. Then he tried to explain the strange thing that had happened, how from coping out he verses of the ancient masters he had begun to write his own. He concluded by saying that when he was old enough, he had left Daxing and took to the road. He did not tell Wang why he had left the capital. As always, he kept to himself the story of his love for the young widow Tian Miao and how, with nothing to offer, he had gone away to clear the path for a well-off suitor who could make her happier.

“Why didn’t you return to your village instead of going on the road?”

“There was nothing to draw me back. My grandfather died when I was a child. I loved him very much. I loved my parents too, but both of them died of a fever while I was learning the classics in the capital and exasperating Master Shen with my bad calligraphy.”

“I see,” said Wang.

“And you? There’s no one you’d be with in Meishan tonight.”

Wang took a deep breath. “My wife died two years ago,” he said stoically. “We had one child -- or we would have. Mother and child died together.”

There was nothing Hsi-wei could say to this, and so the two men sat silently for a few minutes.

Suddenly Wang struck his thigh. “So,” he said in a brighter tone, “do you still write poems?”

“I try.”

“Recite one for me.”

“I’m not used to reciting my verses.”

“Indulge me. Pay for the pork.”

“Very well. I’ll try, if you please. In honor of the Festival, here’s a poem about the moon.” And Hsi-wei recited Yellow Moon at Lake Weishan which later became his most popular poem.

Wang squinted at Hsi-wei, clearly impressed. “You wrote that?”

“Yes, Sir.”

“Well then, now I believe every word of your story.”

Wang stood up and called for a jug of wine.

As they drank, Hsi-wei asked to hear about the complicated case in Meishan. Wang obliged and took obvious pleasure in laying out the whole sordid story. Hsi-wei was attentive, asked questions about the men and women involved and even about some points of law. In this way, the two spent the afternoon, chewing over a criminal scheme and drinking yellow wine.

At dusk, Wang said, “Listen.”

“What is it?”

“Nothing. No rain striking the roof.”

“Yes, it’s stopped.”

“Perfect! Now that we’ve gotten warm and dry and even a little drunk, what do you say we take a stroll through the town and see the full moon? It’s practically a duty to look at the moon tonight.”

Before leaving the inn, Wang bought two small jugs of yellow wine.

The streets and lanes of Yicheng quickly filled with happy children running about with lanterns, young couples strolling hand in hand, and old couples stopping to greet one another. Freed from the last ragged clouds, the full moon showered the town with a silvery light. Here and there, firecrackers were set off and, every few yards, somebody was selling mooncakes. People had set out small altars with statues of the Moon Goddess. Passersby stopped to whisper a prayer for a child or an abundant harvest, for beauty, good fortune, long life, maybe for revenge or the death of a mother-in-law.

The sights and smells of the Festival made the two men reflective, not gloomy but nostalgic.

“This is my seventh Moon Festival on the road,” said Hsi-wei as they watched two young couples laughing together and children squealing as they chased after each other. “In my village, we had special games for the Moon Festival. Have you heard of the one called ‘Encircle the Toad’?”

“Never heard of it. How’s it played?”

“Boys draw straws and the one with the short straw has to stand still while the other children make a circle around him and chant a song -- Long life to the King of Toads! May he rule for a thousand years! The chant’s supposed to turn the boy into a toad -- magic. Then he has to squat down and jump around like a toad until someone takes pity and sprinkles water on his head to turn him back into a boy again.”

“I didn’t play such games. We always spent the holiday at my grandparents’ villa. My aunts and uncles all came. But my cousins were all much older than I was, too old to play with me. My grandmother kept me near her and every year would tell me the same story, the one about how the Sun God and the Moon Goddess are a married couple and the stars their children. She’d point up at the full moon and say that when she looks like that it means that she’s pregnant and when she turns back into a crescent it means that a new star has been born.”

“A pretty story.”

“I used to believe every word of it,” said Wang with a wistful smile. “I’m not sure if she ever believed it.”

They stopped so Wang could buy some mooncakes. He asked the seller if she had any stuffed with red bean paste and when she said she did, he asked her to fill a basket.

“My favorite when I was a boy,” he said and offered one to Hsi-wei. “I liked sweets back then,” he said staring up toward the moon.

Hsi-wei fancied that though Wang was standing beside him in Yicheng he was also back at his grandparents’ villa listening to the story of the sun and moon and stars. Then Hsi-wei thought that it wasn’t so different for him. Though he was chewing a sweet Yicheng mooncake he was also a little boy in the middle of a circle of chanting children.

Their recollections made both men sad but happy, too. Nostalgia is like that.

They continued on toward the main square where they found an empty bench. They sat down with their wine and cakes and watched the lively crowd, heard the greetings and jokes. They felt like a couple of ghosts.

“My grandfather,” said Hsi-wei, “told me a story on the night of the Festival. He must have told it to me every year until he died. You must know it, too -- the story of Hou Yi and his wife Chang’e.”

“Ah, of course. The elixir of immortality. There’s more than one version, more than two. Can you remember how your grandfather told it?”

“I’m not sure I can, not all of it, anyway. It was long ago and it was complicated, like your case of fraud. I remember that the archer Hou Yi killed a monster or a devil of some kind and the gods rewarded him with a vial of the immortality elixir. But then for some reason he had to make a journey and while he was away his apprentice tried to steal the elixir for himself. But Hou Yi’s virtuous wife Chang’e seized the vial first and swallowed it down. Hou Yi arrived home just as she was rising into the heavens and cried up at her helplessly. Chang’e longed to rejoin her husband but could not, now that she was immortal. So, she settled on the moon to stay as close as she could to Ho Yi. According to my grandfather, whenever the moon was full, Hou Yi would honor his lost beloved by laying out her favorite foods in his courtyard. That was how my grandfather explained who the Moon Goddess was and that it is to remember Hou Yi and his offerings to Chang’e that we make mooncakes on the day of the Moon Festival and gobble them up at night. When he got to the mooncakes, grandfather would always pop one in my mouth.” Hsi-wei laughed at the memory.

“Shall I pop a mooncake in your mouth?” said Wang.

Hsi-wei laughed.

“Well, your grandfather had one version of the story,” he said. “The one I was told is nearly the opposite.”

“The opposite? How’s that?”

“My uncle, who had been a Zhou minister during the wars, told me this story. He said that Hou Yi, the great archer, was asked by the gods to go to Shun and slay a monster that had been wreaking havoc there. Things had gotten so bad that the King himself had run away with his family. After Hou Yi dispatched the monster, the people of Shun made him their new king and the gods rewarded him with a jade bottle containing the elixir of immortality. As Hou Yi was still young and strong, he decided to lock the elixir in a special iron box, telling himself he would take it when he began to weaken and feel old. But power isn’t good for some people. The hero the virtuous Chang’e had married, the brave and humane man she had followed to Shun, the skilled archer who had slain the monster, quickly turned into a tyrant guilty of countless cruelties. Horrified by her husband’s viciousness, Chang’e resolved to prevent him from going on harming people forever. So, she broke into the iron box, took out the jade bottle, and drank down the elixir. Then, just as in your grandfather’s version, she rose into the heavens and became the Moon Goddess, watching over the people who worshipped her and prayed to her every autumn -- the men for a good harvest and the women for healthy children.”

Hsi-wei gave a nod. “I like your version better,” he said. “Even though both stories are fables, yours seems closer to the truth.”

“I suppose a poet would know. Don’t you make fables that aim at the truth?”

Hsi-wei acknowledged this perceptive remark with a slight bow and then the two men again fell silent, each lost in his own chamber of memory.

At length, Wang gave a deep sigh.

“What is it?” asked Hsi-wei.

“The story of Hou and Chang’e has made me think about how I won my wife all those years ago. It was on this very night, that of the Moon Festival.”

“If it won’t cause you pain, I’d like to hear the story.”

“Pain? A few years ago, I interviewed a woman whose husband had filed a petition to put her aside because of her constant complaining. She confided to me that the only thing that relieved the pain of her miserable marriage was whining about everything that hurt.”

“Did you think the woman spiteful?”

Wang gave a grunt. “Perhaps, but no more than her husband. Well, I’ll tell you what’s hurting me now and maybe I’ll feel better too. The Moon Festival is a time for match-making and, in our town, there was a local tradition, a kind of formal game for the older children -- more serious than your King Toad in the Circle. On the Festival night, young men would invite the marriageable girls who’d caught their eye to meet them at a certain clearing in the forest outside of the West Gate. The girls would all come early and hide themselves in the thicket. When the boys arrived with their lanterns, they’d compete with one another in praising their chosen girls. This one’s eyes, that one’s smile, another’s virtue, modesty, sweetness -- and the beauty of them all. Then, at a signal, the girls would burst from the woods and go to their sweethearts. If they approved of what they’d heard, they would take their hands.”

“And your wife took your hand?”

“Mmm. She did. On the night of the Moon Festival. This night.”

Hsi-wei was suddenly overcome with homesickness and recalled something that had happened with his grandfather. They were walking through the village and the old man greeted a poor widow by name and discreetly slipped a few coins into her hand. The old veteran did this sort of thing all the time. “Grandfather, why are you so kind to everybody?” little Hsi-wei had asked.

“Because of the people I killed and the more I saw being killed,” was his grandfather’s reply. At the time, Hsi-wei was too young to understand.

It grew late. The crowds dispersed. The lanterns burnt out; the children had all been sent to bed by their parents, and the jugs of yellow wine were empty. The two men got up from the bench and, slightly tottering, circled back to the inn where they bid each other a quick and rather embarrassed goodnight.

There were no farewells in the morning. Wang went early to the magistrate’s office while Hsi-wei slept late and then went to the square to buy straw for the sandals he owed the innkeeper and to try to scare up some customers. Wang didn’t return to the inn. He stayed with the local magistrate that night and left Yicheng the following morning. Hsi-wei stayed only two more days, until he had filled all his orders for straw sandals.

Though the poet’s visit to Yicheng was brief, it did have one lasting result, the short poem people called “Eighth Moon Festival.”

For seven autumns I’d walked the Empire’s rutted roads alone.

But that night in Yicheng, Wang Jiang-guo and I drank together.

We polished off two jugs of yellow wine, glad not to be alone.

We wallowed in memories sweet as mooncakes yet painful to tell.

All night, Chang’e watched over us as if she shared our homesickness.

Kailey Tedesco

Three Poems

“a horror / a vision”

what if, on my porch-end like guards, i had two lions

made of stone? & what if, like in space, where

i become unsure if i am myself or looking inside

myself, one of those lions spoke? i am only partially

fed the dream-blood, but once i’ve tasted

i cannot exhume the lust. oneiric is what you

might call a dress with puff-sleeves, an outfit

worn on the round-bed of a sex motel, overdressed

& applefat with ruffle. what if what the lion said

could bury me into the layers of gown & the layers

of blood & the layers of self that only exist

during the sleeps that paralyze me? all i can remember

is the magma of my nightmare robed in orb,

me spelling the name of my favorite childhood toys

before a mirror like a micro-recital. all i can remember is

the swans playing dead, heads bowed

against the brim of the highway, a corsage

of feather bread-leavened before

our very eyes. i have lost all of my sobbed

candies. all around me, a house monsters itself

from the sounded alarm of an intruder on a crinkling

stairway, from the way my bloodstream

plays whisper-down-the-lane. what if,

like a guard, the lion spoke in devil’s tongues,

gave me books to sign? what if all i ever

wanted was to be protected?

“i was born en caul / i was born covered in fur”

“hagiography”

the whole of my small life glassed in votive --

see me...for what i have done. thank you,

nursemaid, for placing my doubt-cake

in the dirt. now it sprouts flowers,

mulberries itself into an entire tree

of bones you’ll use to.........dig up

weather. this grief subsumes

the way it never does.

i’ve dug my own little holes to plant

the offerings for the demon

for whom i am the legal guardian.

there’s no chicken-feast here,

no natural source of running water.

i am chapel-drunk waving stones

over my plated eyeballs, trying

to find...my old child-dreams

in the trick-bookcases. the toads

will sing hymnals & i will chant

along pitchy with them, my body a shiver

next to your body -- tadpoles,

entire little lives, swimming in it.

i can feel myself knowing

there are so many more

robes to be worn.

Christian Bufo

Three Poems

“Possession”

the big, big trees

of ancient New Jersey

impose on our Freudian telepathy,

demanding nuanced opinions of

a faithful love vs. an impulsive one,

growing up with an older sister

might have helped me through

these pedantic arguments,

I found another mossy

growth up my leg this morning,

the leaves of my skin have

hardened yellow and mostly fallen,

and my roots...

they’re more metaphorical

for I can move about freely

unlike most,

I fragment into the kitchen,

bark in my wake,

like Cronus, I must eat

leafy greens to survive,

I now realize this desire

is not the consumption of the Other,

it’s something similar,

our individual labyrinths,

mobius strips of skin and bone and intestine

are entwined but never touching

“Insecure”

TV static is missing

from the late night drywall,

it’s artificial darkness

would ricochet like fleas

with an electromagnetic nausea,

snow on the nose

of a broken statue,

that faraway foot smell cowers low

beside me as I poise over hardwood,

fishing for socks under the couch,

a typical haunt of mine,

perhaps the dresser could

go for a visit or maybe the

ornamental chair would

appreciate my weight,

the guilt and shame that

embraces this home like dust

flatters itself as insecurity,

it cakes the green bananas, the cameras,

the unread books, the credit cards, the

advil, the cat’s toys, the leather shoes,

the eyeliner pen, the dirty rugs...

I find comfort in knowing

each moment holds stochastic purity,

that this time my hand might slip

through the atoms of my coffee table,

in this ghostly clarity

there is really only me,

laying face down on the floor,

expecting nothing, hoping for everything,

like the evidence of a hand

on a cushion,

I’m locked in place

until touched again,

billowing only slightly

to check my phone

or write some asinine idea

on yellow paper

I wait obediently for

reassurance knowing

it will come,

like pressing a cork back into

a bottle of red wine,

it’s annoying and stains a little

“My Mechanical Eye”

a hand her’s

did grip,

around her three weakest fingers,

wedding ring barely visible,

white dress and white flowers,

veil down to her ankles,

and a despondence that travels

to me through our generational wormhole,

I see her so singularly, this is

the only picture I’ve ever

seen of her anywhere close to my age,

I assure you, I am not mythologizing,

this is a disruption of time,

I’m in a Wizard of Oz tornado across from her,

we’re spinning on two different trajectories,

but for these moments, we appear

stationary and clear,

close enough to touch,

she stares into the camera

in the same way as she does now,

the words on her lips,

just as they are on mine

Konstantinos Patrinos

“An Ordinary Night”

Victoria Mier

“Osteomancy”

I want you to know I went to the stone circle that day because I was always going to go to the stone circle. Please try to understand.

Sister Agnes said God gave us free will. He does not control us like puppets, she explained. We are always free to choose. And that’s the biggest test of all: what we choose.

I did not choose the stone circle, but it’s where I ended up anyway, because Sister Agnes was wrong. I’m not sure if it’s me in particular who was robbed of free will, or if we all were.

Sister Agnes was wrong about a lot of things. Her God -- your God -- could not have prepared me for what was actually out there, for the sick white that gleamed in the darkness, for the things that sat in my marrow like tar stuck to the bottom of a pit.

It all started, I think, when the carnival came to our town a lifetime ago. Sister Agnes told us the carnival would be full of God’s tests. We were supposed to trust in God’s plan for us instead of asking fortune tellers who consort with demons. We were supposed to know that the sweetest treat is preparing ourselves for God, not caramel apples.

At the carnival, the fortune teller looked a lot like Sister Agnes, which I thought was funny -- the same squat stature, wrinkled skin, gnarled hands, and dark, beady eyes. But the fortune teller dressed in purple velvet instead of a habit and wore a tangle of gold necklaces where Sister Agnes’s cross was. I wondered out loud to my friends if they were sisters who chose different Gods. Becca looked at me sideways over her cup of apple cider and asked me how seriously I was taking this. I shrugged.

The fortune teller Agnes waved us into the tent. The darkness was thick and smoky inside, punctuated by a thousand tiny candles. I sat down on the sparkly cushions that surrounded her little table. My friends, it seemed, did not follow.

“What do you want to know?” the fortune teller asked without looking up.

I wanted to know everything. Was magic real? If not, what was the point? Would reality ever wear itself strange and thin for me? I settled instead on something that seemed simpler.

“Do I have free will?” I asked. “Is God testing me? Sister Agnes said I wasn’t even supposed to visit you because of the demons.”

The fortune teller cackled.

“No demons here,” she said, much to my disappointment. “ I suppose we all have free will, right? Let me read your cards. They’ll tell me what you’ll do with that free will of yours.”

The fortune teller watched me now, shuffling the cards in her hand with surprising dexterity. Sister Agnes could barely open a pack of chalk half the time.

“We can be influenced by many things. Karma. Past lives. Ancestors. You, girl, have your ancestors all around you. Calling to you. Pulling your bones like strings.”

The fortune teller dealt one card: a tall stone tower, like the ones they keep Rapunzel in, but with a skeleton lopsided and gleaming at the base of the turret. She tutted under her breath. She pulled another card. It was the same. She stopped and glanced up at me. Then she pulled a third card. It was still the same round, weathered stone turret piercing the ground like a sword. She pulled more and more and more -- I lost count -- until they formed a circle of stones on her table.

“Aren’t they supposed to be different?” I asked, leaning forward.

Her head snapped back and she stared at me. She looked less and less like Sister Agnes. The candles on her table flickered against her hooked nose and her eyes went dark. I swear the cards on the table started to skitter like beetles.

“Get out,” the fortune teller said.

I scrambled to my feet and slapped the twenty dollar bill you had given me on the table. I know I shouldn’t have spent it all on the fortune teller but I was too scared to ask for change. And then I ran to my friends outside.

I didn’t tell them. They wouldn’t have believed me. It’s not like you believed me, either. If you had, do you think we could have stopped it there?

On Monday, Sister Agnes had no answers for me, but she did call you and say she was very concerned about me. You were already concerned about me, of course, because I spent my entire weekends on D&D campaigns at the local comic book shop and you didn’t really get that.

You didn’t like when I found the metaphysical store in the next town over and of course I never told you about discovering the Order of the East’s Temple hidden away in the old, rundown textile factory.

The members of the Temple believed me when I told them the story. They spoke to me like I had an aura of broken glass. They looked at me like maybe for the first time, they would see the kind of magick that every goddamn person in every fucking temple and coven and meeting group is secretly hoping for, no matter how much they pretend they’re not.

But then nothing ever happened and I was just the newbie from the suburbs. Mira, one of the senior members, asked me about my heritage one evening after a long ritual, sipping wine on the threadbare velvet couches that Carey found on the curbside. The beeswax pillars had nearly burnt all the way down, wax seeping onto the concrete floor.

“I’m Welsh, mostly,” I told her.

“That’s a lot of magick and folklore there, you know that, right?” Mira said, eyes locking onto mine over the rim of her red wine, the liquid reflecting her steady gaze.

“Yeah, a little bit,” I said. “My mom doesn’t talk about it much.”

Mira slammed her glass down on the old steamer trunk we used as a coffee table and stared at me.

“That’s it, of course. Go to Wales. Let the bones of your ancestors sing you home.”

I clung to the idea of going to Wales because Mira told me to. She seemed like she knew more than me and could recite spells without looking at the book and draw perfect pentacles from memory. When I told you I wanted to study abroad, I think you immediately stressed about the cost, but I finally wanted to do something normal, so you told me you’d figure it out. The scholarship figured it out for us.

When I arrived, my bones did sing there, a lilting kind of hymn at the castle on the hill and the little tea shop tucked away in an alley. Mira had been right. I waited: for a black dog on a moor, a hooded man on a misty day, an invitation scrawled upon a curl of vellum.

Nothing happened. Weeks passed. The marrow song spiraled out of reach.

“Have you seen the countryside?” slid across my screen one day, a message from Mira. Before I could answer, my phone was pinging with links to different places -- castles and cliffs and burial tombs. None of them made the song louder. But I had a sudden, sinking feeling that if I went back home and told Mira I had just waited around for something to happen, she wouldn’t like me anymore.

“I’m planning on it!” I wrote back. There was an upcoming bank holiday and our professor had encouraged us to enjoy the long weekend.

A henge had already claimed me, of course, but I couldn’t have known that. So I made it out like I had done the choosing, printing all the sites’ pictures out and spreading them around my flat, blissfully empty with my roommates off to Ibiza. I prepared a cup of loose leaf tea with the kind of tender and wild ritual that even Carey would have been proud of, I think.

And then I drank it. Sometimes we do know how things are going to end: the cup of tea consumed, the bone-white china left somewhat maligned by the haze. The swollen black leaves at the bottom where they belong, the wet white gleaming. Let this remain.

I stared at the leaves until I saw something, glimpsed an outline or impression. I told myself it looked like a stone circle just outside the city with a wide altar stone and tall, square slabs.

It didn’t. Instead the tea leaves showed me a crown of small stones, stout like towers, studded into the grass. What I mistook for the altar stone was actually the cairn and the burial chamber. And, of course, the bones. I didn’t know. I swear I did not.

(I have always known.)

I rented a car and told no one but Mira where I was going. It took me an hour. There was a parking lot and an information board and a little fenced path.

There was no sacred hum in my bones, no lilt to the wind, no whisper in my ear that said, “you are finally home and now your secrets will spill out like wine and you may drink until your head is sore and your tongue is black.”

I walked around the circle. It was just a bunch of rocks. They were pretty. Lichen-covered. A few other tourists milled about. The tall grasses swayed in the late summer light.

I hated it and I got back into my car and drove off without ever looking at the map or the directions printed out the day before. I just drove. At some point, the rage faded and I was lost. I pulled off onto the side of the road.

A knock came from my passenger window and I jumped. A man stood there -- seemingly materializing from nowhere -- so I rolled the window down a crack or two and glared at him.

“Pardon me,” the man said. “Are you lost, miss?”

Silence stretched tight over the gravel road and the swaying grass and the setting sun.

“I’m on my way to meet some friends to check out the stone circle,” I said finally. “I think I missed a turn.”

If I could just get back to the stone circle, maybe I could try again. I had been ungrateful. Otherwise, I would have nothing and the dreams would come back and no tarot deck would ever turn itself inside out for me again.

“Oh, no,” the man said with a shake of his head. “You’ve gotten a bit ahead of yourself. Go about a kilometer up the road and take the first right. In about another kilometer, you’ll see the parking lot on the left.”

I pulled back onto the road. When I looked for the man in the rearview mirror -- I don’t know what made me do it -- there was no man. At first, I saw only an open field, the treeline in the distance, and the gravel road. But the longer I stared into the mirror, the more the world opened up to me, and where the man had been, I saw something that was not a man at all. I know what you’re going to say. But I saw it.

It was maybe three feet tall with strange, pointed ears, skin black as coal ash, the eyes red like a sailor’s warning. I stared, wondering if I could possibly be looking at such a thing, before a horn sounded. I had drifted into the other lane. I righted the car, my mouth dry, and then I looked in the mirror again.

Nothing.

My hands stuck to the steering wheel as I followed the rest of the directions. I thought that I shouldn’t, considering what I’d seen, but no matter how much I tried to stop -- I tried to stop, didn’t I? -- I stayed the path.

It was not the same parking lot I had been in earlier. The light was slanted now, the horizon tinged with dusk, and the wind had changed, thick with rotting leaves and damp earth. No information board greeted me, just a path, well-worn, cut through the grass like a scar. I followed it.

You would have followed it, too. You think you are better than me, smarter than me, you think that your mind would never contort a man into a púca, that you would have never followed a slim dirt path, pale as bone.

You are not better than me and your cards never turned to towers and you have never wanted to shake off your flesh.

The path crested over a hill that rose out of the earth, taking me down and down before I finally saw it, nearly hidden in the grasses, obscured by what looked like a natural depression in the earth, a wide and keening place.

It was, of course, a henge -- a henge like a crown of thorns. The stones were buried deep in the earth, pointing outward at an angle, barely rising to my knee. They were nothing to be afraid of, I told myself.

And then I saw where the depression sloped, where the cairn was piled high over a deep and gaping maw. It was the burial chamber. I walked toward it like maybe it was the only thing that had ever been real, something buzzing in my ears.

I could hear the bones singing. They called me, so sick and sweet, and they bid me to complete their transformation. I sank to my knees, a supplicant, and I began to dig like they knew I would. The dirt slid under my fingernails and I shuddered with pleasure. I dug until I thought I might be ill. I dug until I found the bones.

They are mine and they are yours. They are our pickled and skinned bodies cast into the maw to keep the darkness at bay, to be honed until we gleam, until we are bright and sharp enough to turn back the darkness.

Someone tried to stop me, yelling something in my face, but I did not stop. I could not stop. Did they not know I was chosen, ordained, born to bear the bones of my ancestors back to the surface where they could finally complete their task? Could they not feel the song crescendo with each aching rib I freed from the darkness?

Could they not see this was divine?

As the night came roaring in, sickly white spots studded the wild expanses of the velvet darkness above me. I had always thought they were stars because you told me so, but I know now they are bones, tiny bone fragments, broken and brave and flung into the sky by those who came before me. Guided by their light and their song, I built my palace, joint-in-joint, careful and glorious. My palace gleamed -- it gleamed sick, sick, sick in the bright starlight, sharp as a knife and sweet as sin.

You visit sometimes. You are always sad. I suppose it is because you want to be like me: exalted, feasting upon bone studs in translucent cups carved from the air itself. To think you almost stopped me from being what I am.

You leave before nightfall comes. Then I am alone and whole. I am ordained and my purpose is divine and I walk those strange shores beneath the dirt. I am in my favorite tower, where everything is white and perfect and I have never desired for anything.

It is here that I will wait until my pickled and brined body falls away. Then I, too, will be flung into the sky: a sharp-eyed star to hold back the darkness, gleaming like swollen tea leaves at the bottom of a bone china cup.

Please try to understand.

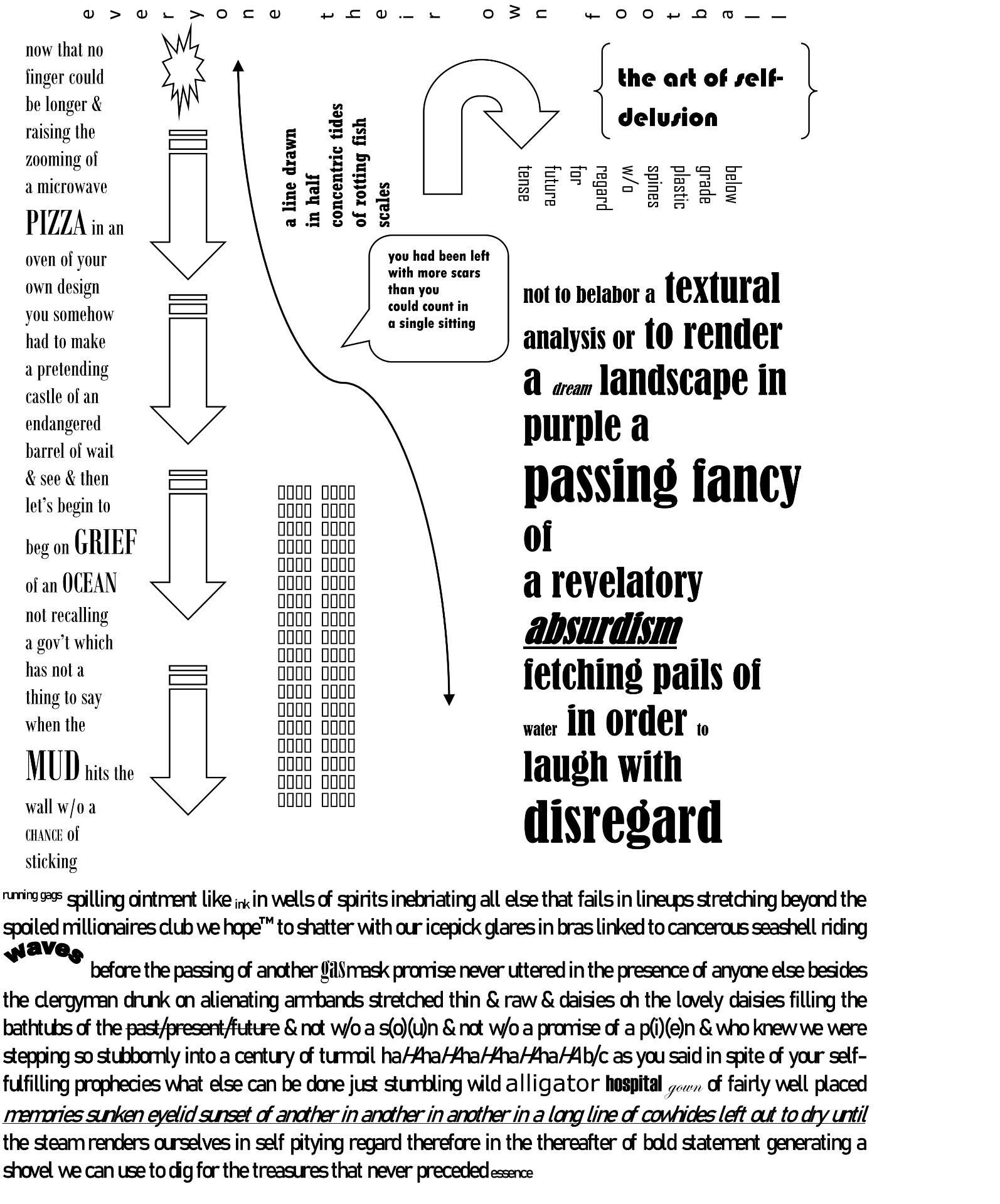

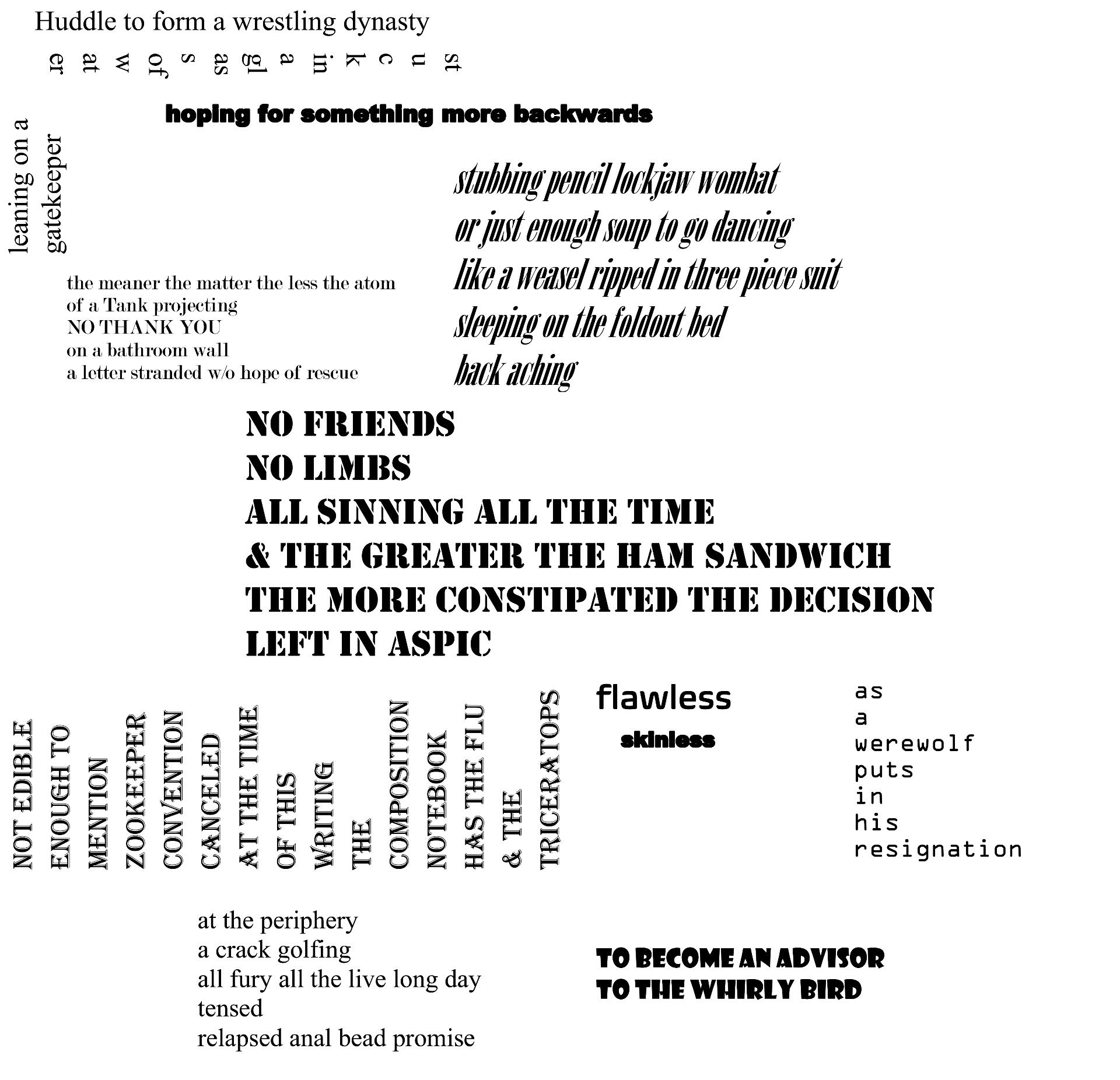

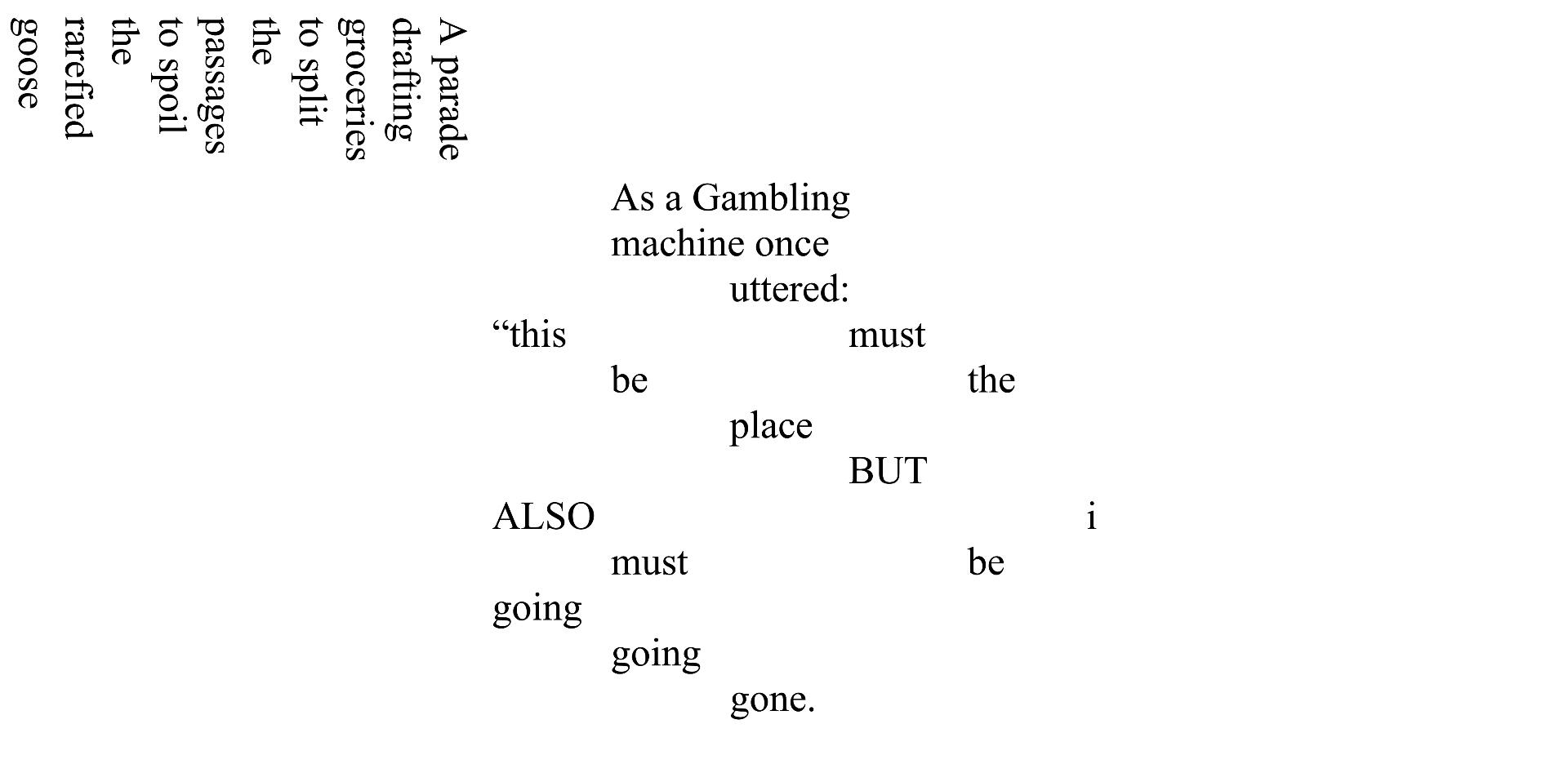

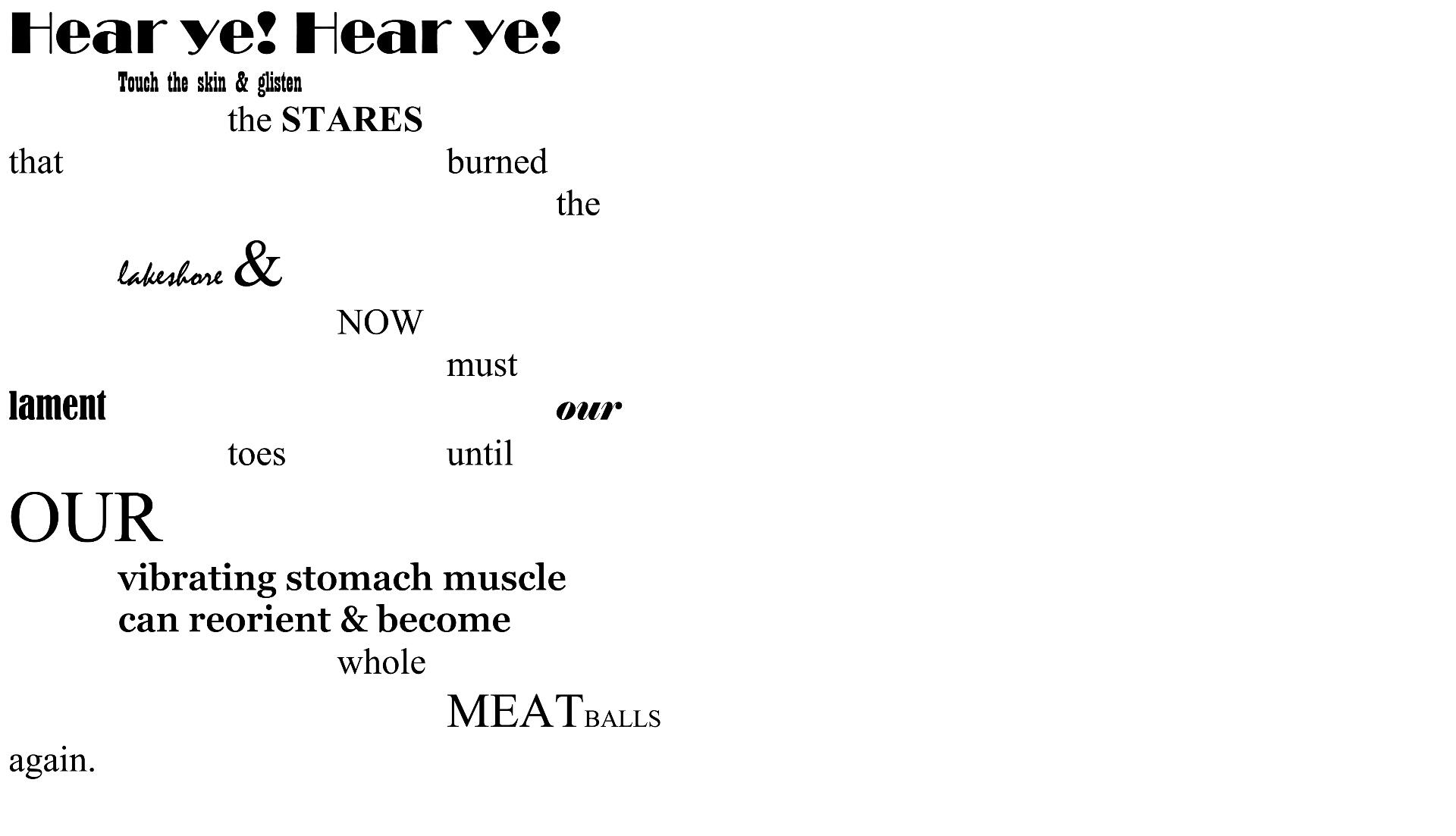

Joshua Martin

Five Art Poems

“Banality ©”

“<dangling from the end of an ear>”

“Bags&bags&Bags”

“Rafts and Other Thermal Variations”

“<As><To> The Age of Reason Collapsing”

Shine Ballard

Two Poems

“As Nature Will—s”

“Precious Relics”

Warren Longmire

Three Poems

“This is the last time, I swear”

.............................................I don’t know what

.............................................I’m supposed to know

.............................................I just know in code.

..............................

...............At Vertex, we call one browser tab worth of inputs a scene.

...............Each scene is collected into CRUD functions: representing a creation

..............................reading, updating or the deletion of a resource

..............................of which there are almost 50 max.

...............My resource at Vertex is the taxpayer. A taxpayer is an

...............entry type, a start and indeterminate end date and

..............................a reason code. My HP laptop clicks into half cubes

..............................with a heavy plastic switch reminiscent of classic ThinkPad.

...............Every morning: two monitors on articulated arms. One in

...............landscape shows the scene where my client edits

..............................the taxpayer. Applies a discount code. Verifies

..............................their taxability. Identifies multiple jurisdictions of possible

...............equivalent levy items rendered in scrolling blue combobox

...............after they are fetched from our backend team’s API:

..............................the Local Imposition Tax of the Cocopah

..............................reservation is a district in Arizona.

..............................

.............................................I don’t know what

.............................................I’m supposed to know

.............................................I just know in code.

..............................

...............My second monitor is in portrait mode. Red warning

...............text says I need another space after line 305’s colon.

..............................The taxpayer logs of the object inside and object we are

..............................defining is the unique key when tagged with a dollar sign.

...............Our Fooda app lunch program says American

...............Halal is serving us today. We slouch

..............................eating lamb drowning in white

..............................while CNN captions what is breaking.

“No one knows what they are doing at Microsoft.”

No one knows what they are doing at Microsoft.

No one knows what they are doing at Electronic Arts.

No one knows what they are doing at the Disney subsidiary tucked in the zone 3 London exurb

...............where the lighters hang math in the wireframes

...............and the render farms run hot calculating an animated bird’s articulations

...............creating a story of English war propaganda backed by the voice of Ricky Gervais.

No one knows what they are doing when the consoles upgrade

...............and programmers invent new ways to display bullet shine

...............locked in their anime lined fabric cubes and corralled into bullpens

...............for 60 hrs a week with no overtime.

No one knows what they are doing at Amazon

...............where somewhere in North Virginia, Available Zone 1 detects a spike

...............and the night watchmen breathes the antiseptic sheen of a clean router box

...............spitting some ardent startup’s mockup of a God.

No one knows what they’re doing in the incubator inside

...............the insurance company that owns a stake in Beyonce’s thighs

...............where a depressed CEO’s child thinks it’s dad job to leave

...............where the flock of failed musicians he bought

...............were rebuilt in bootcamps of the mind

...............and poured a margin of excess into a spreadsheet cell

...............approximating time of death in a box.

“Startup 2021”

Imagine hearing one held C struck in a plush hotel lobby

no, in the clean regulation sized ball court in the bottom floor

the walls are white

remove the walls

the floor is blank

imagine blank, soft drone and a womb-like suspension and one piano

a piano with one key

a hung key the size of your leg

long and smooth as expensive milkshake

that hugs the pressure of hand like your proud

dad’s first high five.

A flesh smooth button that gives like that. Even and

hand crafted with a black box

hidden deep in the calm, wave growth in indigo pulse

and that centering ding that

floats into infinite like a boat

miraging into the horizon.

Give them:

one press, one note, whole empty visual everything else

and then cut to logout in 10.

That’s our hook. The sudden release.

And then they attach to their machines again.

And then we open the pod bay cacophony and they

get back to work, their lunch spent and get

locked in the church

four more hours.

Nice? Clear.

So I’ve got this thing in my basement.

How much do you think

they would pay?

Stephanie V Sears

Four Poems

“Dying a Motorcyclist”

You had already died

when we met,

already dense like granite,

a statue shadowed by the froth of leaves.

Unable to reach beyond youth

-I guessed it-

an epic carving

profiled in the bronze cladding

of a palatial staircase, though

still you lived in the wildest places,

chiseled down

to few words and

a hot, reverberating sadness

that was your dignity.

You wore campfire clothes

color of thatch and mud

crannied with pockets.

In your mordoré eyes,

gilded raptors,

a feathering of fronds

induced by warm seas,

that last rush of enticement.

After that your tires traced a Z

in the mud, and off the caldera's cliff

into the waterfall you went.

“Eclipse”

Summer stars revolve clock-wise

In empires of certainty

For eyes that are full of breeze

Tranquillized in foiled darkness.

Clear, the universal cave.

Intuitive, the cricket radars.

Seraphic the breathing,

Seductive the pathos

Of distance crossed over by proximity

On night’s tablet

Of all calculations.

Enlightened promise

Of coinciding minions

Drumming the tattoo of oneness.

The sky exuberates with shortcuts.

The moon butters up the sea.

A complacency all the way

To infinity’s fault-line.

At the eleventh hour, a quiet

Rebellion heaves at the core

Of peace.

The moon becomes

Half a rogue.

Night loses its bearings --

Four hundred Incandescent

Wings tumble --

Collapses onto itself,

Sulfuric with recantation.

Night forages through perdition

Siding with

Unabridged truth.

“In the Silence After the Bird's Call”

Island mountain on an intemperate sea,

in a tapestry of fog

hollowed by silence: an armored safe

locking in enchantment.

Mystery guards the code,

prudence hides the beast,

mist fills my eyes.

How not to recognize

disguise in such torpor?

Inland from ocean’s recitations,

just after the Barbet’s overture

to my hopes beside a pond

as quiet as a dormitory,

I wonder: ‘is it so?’

Waffling through intuition,

my instant hangs on,

suspects a rainbow of skins.

Rafts of vapor lift me

to hyphened parapets of insight.

Nature draws clouds on itself,

paints in a youth

of mischief and coyness.

A careening in the branches,

a long tail act,

a mottled gymnast.

‘You’re still here’, sighs relief.

“Laurent”

Of that cool blaze between trident and chariot

beyond the frayed edges of purpose

and the inflexible timing of beauty

red boy with shoal green eyes

is forever maker and master.

Sun freckled, salamander slim,

woodsy beneath the Mape trees,

streamlined with island solitude

begotten by a Polish girl in need of time

a Frenchman failed to give her,

lost to them, elsewhere

in the mind of a dreamer

unburdened by age.

Converted to ecclesiastical ferns,

baptized in leaf fountains,

with a child’s limbs taking to

the black armored peaks,

fastening orchids to combed falls,

amphibian at sunset

when fish hop like hares,

at night sizing stellar carats

strung between sand-bottomed trees,

spellbound by the fey likeness of himself.

Luke Condzal

“Two Tourists”

Two young American bozos: the short stocky bald one, Face Rimolopolous, his destitute ancestors having hailed from the Greek Isles to wallow in the blood and fat of Manhattan’s diner business, waddled in wide struts, a bare tanned dome round as an avocado pit glinting neon with vice against Bangkok’s red light district, or the first of the three the pair intended to visit that night; and a foot above him the tall one, a Mongoose Toastgaard, good old Wyoming boy: narrow but sturdy he hardly survived the swelter; still his good will stayed inviolate and above a burned forehead his blonde hair stood unruly, the pretty yellow remains of childhood, a thick pelt there to warm him (as opposed to his partner in crime who, without need for hair except on his back chest neck and hands, gathered sustenance from the sun via his barren scalp) along the snow caps and high peaks of his vascular Scandinavia, where some generations ago his pale skin might have likened him to the blue ice enough to hunt in stealth its leopards with spears or bare hands and make shelter of their skins, ornaments of their entrails. They stumbled out of their tuk-tuk, both hit their heads on the low bar of its roof. Unscathed though did they remain on their hunt for what could easily be perceived here, on this little street stained and glimmering, wafting the deep odors of humans and fish, as wholesome fun.

It wasn’t as though they hadn’t been already exposed to or engaged or indulged in this kind of activity during their travels together. But always it came about in a nervous way. Face would insist they go down a chosen street one more time, his red cheeks hairy and mouth dry, by then, in what would be their fifth or sixth stroll down the same drenched stretch of asphalt, they browsed ceaselessly the same human catalogue, made commodities of the various masseuses perched with solicitous limbs and playful taunts outside the dozen or more establishments, speaking to them on a first name basis, having perhaps already the night before on a preliminary moonlit casing exchanged contact information, promises of future business. He would invariably wonder aloud if, after working up such a sweat in investigation, might they want to have another meal first. Meanwhile Mongoose would make intermittent claims about sitting this rendezvous out, he had had enough, and in the suspensory moments between such revelations of guilt and penance declare boldly his eternal affections for a masseuse double his age who had batted false eyelashes at him. Sometimes they would decide on a place, sometimes they would give up and go eat pork and drink beer. They fed pangs of hunger, soothed battered dignities and prolapsed egos, sat to rest lower backs aching from stiff hostel beds and heavy backpacks. And with each meal, each bite, each variety of animal protein devoured, they nourished the greedy colonies of hook, tape and pinworms that had swelled obscenely in their bellies and infected their temperament, medication an utter failure, zero reprieve from the wiggling purple and white wrath inside the toilet bowl -- at first terrifying but before long a quantifiable badge of honor to be dealt with later back in the States, land of food processed beyond contamination, of soft sheets and bright doctor’s offices, land of cures for curses, they thought.

Tonight, though, bloated guts patted, tongues salted, they were determined to experience, instead of a back alley relegated to carnal fondling and clumsy intercourse, a spectacle of human sexuality that included lights and drinks, actual discourse with less of the transactional wretchedness they found in the parlors. So, go-go bars it would be. They were moving up in the world, sophistication unbounded.

Immediately they were disgusted with the clientele. Old and fat and balder than Face the lot of them were, and somehow, despite the grandness presented to the fellas on the internet -- a clean and colorful haven for prostitution, for severe observation -- and even amid the relentless pinks purples reds blues whirled against the sky, the grime consumed them. Myriad exposed buttocks glistened iridescent atop stools of dull metal. Refractions of the flesh crossed smokey windows beyond which obscure figures danced and mingled. Vivid pinging of half-dead speakers. Heedless chatter of high heels and negotiation. The hushed musings of awed men too old for throbbing lights, but never too old or too fat or too bald to be lonely, to risk the true prospect of disease for companionship and glitter. All of it noise, all of it musky, all of it registering silly and confounded around them, the young men. And below, the ground stood sticky. Soiled illuminations of littered cigarette butts, painted streaks of steaming vomit. Place of sex, place of fluids, they conceded to each other optimistically.

Down the street the two went. Tented stands lined its middle. Blanket displays of mangos, sticky rice, skewered fish, dildos, ball gags. Each opposing side had its various desultory spots, some perverse constellations shimmering, some the dark corridors of pleasure, desire, torment.

A wiry local man without too many teeth approached them and presented a black index card with purple writing, a small menu describing remarkable acts of vaginal acrobatics: pussy shoots ping pong ball, pussy ties shoe, pussy smokes cigarette, pussy sings song, and more. They had seen and heard of these places before, but not yet ventured into their seething abyss. Face, jaded from his city upbringing, usually skeptical and standoffish with the pervasive street salesmen, when he caught a glimpse of the menu, grabbed it and exploded into a fit of uncivilized laughter.

“Come,” the man said. “You can look and see for free. If you like, you stay.”

Mongoose, always gregarious, put a big hand on the man’s shoulder and took a look at the menu for himself. “Pussy ties shoe?” he said.

“Come and see. Free.”

Face stiffened up. “No, we’re good.”

“We wanted to check one of these out anyway.”

“Not here.”

“Where, then?”

“Come and see,” the man said.

Face sighed. Before he had even verbally consented the man had whisked them through the crowd, through the lights, towards an open doorway, a steep stairway to a high dark void. Outside sat two men on stools smoking.

The tourists looked at each other. They would scope it out, stay for one drink, then press on. Following their guide up the moaning stairs ready to give out, they emerged into a moist dark room, appallingly quiet. Instead of action and movement, as they had anticipated, there was no one behind the bar, were no patrons in sight, the place brown and mournful except for the pinkly lit stage where a few naked or half-naked women stood waiting, awkward and degraded. Closing in on them were walls dilapidated and covered in swollen plaster, the vague remains of chipped paint crumbling black. The ceiling dipped and drooped in the middle as though the floor above were flooded. Unclaimed shadows moved around. Punctuations of hollow space came and went darkly, fluidly, in bouts of bright smoke. Face and Mongoose froze up, prepared to turn around, but at the man’s earnest request ordered two whiskeys. They sat along a couch with a crude metal back, the tatters of its red leather cushion bound in flimsy tape, the wilted fuzz still exposed, still spilling out from inside.

By the time the man had brought their drinks and quietly disappeared, one of the dancers had sat down, naked, next to Face. Mongoose watched transfixed as a woman on stage pulled a necklace of dog tags out of her vagina, the last of which she used to slice through paper.

“You never heard of JFK?” Face said to his girl.

“No.”

He tried to pull up a picture of him on his phone but couldn’t get service. “Handsome young president. They killed him. They shot him in the head.” He mimed it with his hands.

The woman shrugged.

Mongoose sipped his whiskey and noticed on the stage, as woman after woman presented miraculous vulval gesticulations, one in particular, the least naked of them all and most beautiful, stood by absently. She rocked her hips, shuffled her feet, but did not partake in the demonstration.

“How about Martin Luther King, Jr? They killed him too. Blew his brains out.”

Mongoose finished his drink, looked to see Face’s finished too.

“What about Elvis,” Face said. “You never heard of Elvis? He died on the toilet.”

He nudged Face, couldn’t immediately get his attention. The beautiful woman in her pink undergarments suddenly stood over him. She put a lithe fist to her slack jaw and mimed a blowjob, nodded to the bathroom. Moongoose blushed and shook his head. Chills and sweat slithered down his spine.

“Let’s split,” he said to Face, expecting protest.

“Okay, yeah, let’s go.” He looked to the beautiful woman. “Can we get the check?”

Her lackadaisical stance went rigid, wide, powerful. “Pay now,” she said in a robust baritone.

A stout middle-aged woman materialized next to them, dressed in dark velvet layers that added to her imposing girth. She put a firm hand around Face’s wrist. At this point he was used to being man-handled, had even come to enjoy it. “Pay over here.”

“Can we just give you the cash? Here we have it,” Mongoose said, taking out a few crumpled bills from his pocket. Face was already halfway to the stage, so Mongoose followed. The madam let go of his wrist and presented a calculator. She looked at them, then the room and the languid girls, as though she were performing some kind of mental calculation. She typed out on the calculator 30,000 X 2. Sixty thousand baht, or two thousand US dollars. Far cry from the already inflated six they would have paid for their whiskeys. Face looked at the number and laughed.

“What?”

“You pay. Now,” she bellowed. She was about Face’s height; Mongoose towered over both of them. The beautiful woman with the deep voice watched with crossed arms from the other side of the stage.

“What are you talking about? We just got one drink. We’ve been here five minutes.”

“I lose money!” She produced the menu and went through the list of feats, rattling off numbers next to each one. “You saw. You have to pay. Pay now.”

“We don’t even have that much money.”

“ATM outside.”

“How about we give you 3000 Baht, okay?” Mongoose said and took it out from his wallet. She snatched and pocketed it.

“Fifty-seven thousand more! You pay!”

“We don’t have it.”

“ATM.”

“Okay,” Face said. “We’ll go to the ATM and come back.”

“No.” The madam took hold of Mongoose. “He stays. You go with him to ATM,” she said, referring to a pudgy man with short spiky hair fermenting in the shadows.

Moongoose tried to pull away from the Madam. “Look, we will both go. Let us both go. We will come back.”

She slapped him in the stomach. His neck turned blotchy, as it tended to when he became flummoxed. Revelations of rage drawn on the flesh. She pinched one of his nipples and twisted her fingers. “You stay!” She took out a walkie-talkie and said something in Thai. Muffled voices beamed back angrily. “I call --”

“Okay, fine!” Face said. He looked at Mongoose simmering red. “Okay, I’ll go to the ATM. Fine? Yeah? You stay here.”

“I’m not paying a thousand dollars, man.”

“We can afford it, can’t we?”

“I’m not paying it.”

Face postured. “No, you’re right, fuck that. Of course not. Just let me think. Let me scope it out downstairs. I can’t think in here. Is it okay for you to stay? You alright to do that?”

“Yeah. Just -- yeah.” The madam flicked him in the balls and repeated her commands. “If she hits me again… I gotta tell you I’m about to fly into a rage.”

“Just be cool. I’ll be right back.” He looked to his pudgy escort. “Come on.” They left the madam and her beautiful side-kick cornering, tugging at, gripping Mongoose. His head high up above them gagged and lolled with each painful iteration of fingers and palms, the trimmings of barbed nails.

Outside they stopped before the two walkie-talkie equipped guards on stools. One was asleep with a lit cigarette dangling from his mouth. The escort woke him and the drowsy guard staggered to his feet, nearly toppled over, looked at Face through bleary eyes, his partner unmoving. Face held the gaze until his escort shoved him down the street towards the ATM.

“Get the money.”

Face looked around. His hands shook, thick sweat poured off his scalp. He considered taking out the cash, but took out his credit card instead of his debit, jammed it into the machine to buy time.

“Get it.”

“I’m getting it.”

The escort fiddled with his walkie-talkie. Voices clipped in and out.

Face took his card from the machine. “It’s not working. I don’t have enough. I have to go back and get my friend. We have to use his card.”

The escort slapped him on the back.

“I don’t have it. Take me back. I’ll stay upstairs while he goes. You can take him, whatever you need to do.”

The escort tensed his jaw and tried to get through on the walkie-talkie to no avail. He shoved Face back towards the clip joint. On his way in Face stared again at the guard.

Up the stairs and into the room, Mongoose was gone. The madam approached Face with a smirk that told him Mongoose had either fled or was dead.

“Where’s my friend?”

“You have the money?”

The escort spoke to the madam.

“In the bathroom.” She signaled to the other side of the room. A vented door confounded with graffiti, markings, peelings. Positioned right next to the door was the beautiful woman. Leaning on one round hip, she hummed deep melodies of doom. “Where is the money?” the madam asked.

“I have to get it from him.”

Her smirk turned flat. “No money?” But she didn’t grab Face as he walked to the bathroom.

He barged in and found Mongoose not dead or shitting out worms but bent over, brazenly stuffing all his cash into his sock. “What happened?” He noticed raw bruises on Mongoose’s arms, neck and cheeks, tall hair gone mad.

“Dude, they gotta stop fucking hitting me. I’m about to lose it.” He rose.

“Listen” -- he put one hand on Mongoose’s chest, the other behind his neck to pull the high ear to his mouth -- “we’re busting out of here. They got nothing on us. Look at us.” He pulled back. Mongoose’s eyes were wide.

“Yeah? What about downstairs?”

“We got it. They’re asleep down there. On the count of three we burst out of this fucking door, barrel through -- and we keep going no matter what. Don’t stop. We just keep running when we get outside.”

“We just bust through. I’m in. You’re ready?”

“Let’s go.”

The tourists slapped hands and hugged, turned around, shouldered through. Their fast intentions clear to her, the beautiful woman stopped humming and grabbed Face in a bear hug. The madam and the escort ceased their arguing and formed a human barricade a few steps up when Mongoose yanked the beautiful woman off of his friend and threw her down. She landed head first dully against the hard back of the couch. Her head veered sideways over her shoulder as the neck broke with a sharp pang on the metal. A limp mess of contorted flesh dropped to the floor. Mongoose stopped for a second to see what he had done but Face pressed on. He rammed into the madam and knocked her down as the escort clawed him on the back of the neck. He turned around, took hold of the doughy escort’s head by the hair with both hands, dragged with it a resisting body and slammed it into the closest wall repeatedly until it had broken through the plaster into the brick behind it, and caved in itself to reveal skull and the tangled lacework of excavated brains. With one final thrust he left the deflated head lodged in the wall, the body destined to hang below the hole convulsing in dire spasms, its feet crossed and fists clenched. Presently the madam had risen and was brandishing a knife in sudden fear. She lurched away from Face as he went towards the door, but a heavy stool to the back of her head made her fall down woozy. Her knife skidded across the tiled floor and she tried to crawl away. Mongoose, wielding the stool over his head upside down, planted a foot on her back and brought the stool down upon her head, flattening it like ground beef. Teeth and fine shards of skull scattered like dice and glass over the spitting black blood. Mongoose hurled the stool across the room. It clattered, then the room went silent.

“Let’s go,” he said.

Face, opening the door, stopped abruptly. “Wait.”

“What?”

Face walked over and picked up the knife. Taking hold of the madam’s hair in a fist he yanked her crushed head off the floor, the nasal bridge dislodged, white bones braided red, eyeballs emulsified, put the knife to her hairline and carved his way through until he had peeled off a dollar sized tuft of scalp. He held it by its black hair, the naked dancers watching horrified from a pinkly lit huddle, and presented it to Mongoose: the bleeding flesh a pale sliver of light in the gloomy dark of this side of the room. He stuck the sopping human trophy in his pocket and dropped the knife to the floor. They high-fived again, this time with sodden hands, and went on down the dark stairs, shoved the startled guards out of the way. They outran them with ease then proceeded on with their plan for the night, to the two other red-light districts and their many bars and daring performances, two American tourists baring in silence and celebration the enormity of their savagery to the city abroad.

Contributors

CHRISTIAN BUFO was published in E·ratio and has work forthcoming in Stone of Madness Press and Impossible Archetype. Born first in Cherry Hill, NJ, they grew up in the suburbs of Philadelphia. As an infant, they felt especially unlucky at this turn of events, for they longed for New Jersey. However, they still live across the Delaware River in Philadelphia.

JOSHUA MARTIN is a Philadelphia-based writer and filmmaker who currently works in a library. He is the author of the book Vagabond: fragments of a hole (Schism Neuronics). He has had pieces previously published in The Vital Sparks, Breakwater Review, Ink & Voices, The Free Library of the Internet Void, and Paragraph Line. His films have screened at various film festivals including The Pineapple Underground Film Festival, New Filmmakers, Film Al Fresco, Views from the Underground, and The Shooting Wall Film Festival.

KAILEY TEDESCO is the author of She Used to be on a Milk Carton (April Gloaming Publishing), Lizzie, Speak, and FOREVERHAUS (both White Stag Publishing). She is a senior editor for Luna Luna Magazine and she teaches literature and writing in Bethlehem, PA. You can find her work featured in Black Warrior Review, Fairy Tale Review, Gigantic Sequins, Passages North, The Journal, and more. For further information, please visit kaileytedesco.com.

KONSTANTINOS PATRINOS holds a Master of Arts degree in social sciences from Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany. He is a high school teacher for political science and philosophy. His master’s thesis on the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard was published by Logos Verlag. He lives in Berlin with his wife and daughter.

LUKE CONDZAL was born and raised in Manhattan and currently lives in Brooklyn. In addition to writing fiction, he pseudonymously created and performed in the comedy web-series, "Lawrence Korey: Native New Yorker."

ROBERT WEXELBLATT is a professor of humanities at Boston University’s College of General Studies. He has published eight collections of short stories; two books of essays; two short novels; two books of poems; stories, essays, and poems in a variety of journals, and a novel awarded the Indie Book Awards first prize for fiction.

SHINE BALLARD, the fainéantmanqué, currently creates and resides on this plane(t).

STEPHANIE V SEARS is a French and American ethnologist (Doctorate EHESS, Paris 1993), freelance journalist, essayist, and poet whose poetry recently appeared in The Deronda Review, The Comstock Review, The Mystic Blue Review, The Big Windows Review, Indefinite Space, The Plum Tree Tavern, Literary Yard, Clementine Unbound, Anti Heroine Chic, DASH, The Dawn Treader, The Strange Travels of Svinhilde Wilson (Adelaide Books, 2020), and Dodging the Rain.

VICTORIA MIER is a writer, independent bookstore owner, and antiques dealer. She was published extensively as a journalist in a previous life (The Philadelphia Inquirer, Philadelphia magazine, The Reading Eagle) but these days you can find her fiction and poetry in Luna Luna magazine and A Witch’s Craft zine, as well as Vulnerary Magazine later in 2021. Follow her on Instagram on her bookshop's page, @spiralbookcase, for unhinged book reviews and pictures of the shop cat, Calliope.

WARREN C. LONGMIRE is a writer, software engineer, and educator from the bad part of North Philadelphia. His writing has been published in American Poetry Review, Eleven Eleven, The Painted Bride Quarterly, and the upcoming Best American Poetry anthology of 2021. Warren likes jazz, being black, video games, and suffering. You can find his work on Instagram at @alongmirewriter & @doubleyoulongmire.

Support Ocean Conservancy

SORTES supports many local, charitable, and community-based groups -- including Ocean Conservancy:

The ocean has protected us from the worst effects of climate change. From the beginning of industrialization until today, the ocean has absorbed more than 90 percent of the heat from human-caused global warming and about one-third of our carbon emissions. But we are now seeing the devastating effects of that heat and carbon dioxide.

Ocean Conservancy is working with you to protect the ocean from today’s greatest global challenges. Together, we create science-based solutions for a healthy ocean and the wildlife and communities that depend on it.

Charity Navigator rates it four stars:

Founded in 1972, Ocean Conservancy promotes healthy and diverse ocean ecosystems and opposes practices that threaten ocean life and human life. Through research, education, and science-based advocacy, Ocean Conservancy informs, inspires, and empowers people to speak and act on behalf of the oceans. In all its work, Ocean Conservancy strives to be the world's foremost advocate for the oceans. Ocean Conservancy's four strategic priorities reflect the critical ocean conservation issues that will be the main focus of our efforts, including restoring sustainable American fisheries, protecting wildlife from human impacts, conserving special ocean places, and reforming government for better ocean stewardship.

The people who have worked on this publication support this cause and we urge you to as well!

Thank you!

Submission & Contact

To submit or send comments, questions, or suggestions, please email the editors at

SORTES is a spinning collection of stories, poems, songs, and illustrations to help while away the wintery June nights. It’s an oddball grabbag wunderkammer mixtape offering distraction and refreshment.

Each issue is its own creature. We have neither theme nor scene. We like whatever makes us shiver, plotz, turn on, and/or freak out. We've published what might be called magic realism, dirty surrealism, fantastical biography, experimental poetry, tender balladeering, elusive allusive elliptical poetry, and sweet ol grainy photography.

We will periodically host contests, readings, calls for entries, and other spry gimmicks to keep things interesting. Previous issues are available via the site’s Archive link.

#

SORTES considers unsolicited submissions of poetry, prose, illustration, music, videos, and anything else you think may fit our format. Feel free to poke us; we’d love to find a way to publish dance, sculpture, puzzles, and other un-literary modalities.

SORTES is published quarterly. Each issue includes approximately ten works of lit, visual, or performance art. We like a small number of works per issue: artists and readers should have a chance to get to know each other.

SORTES, you’ll notice, is primarily a black-and-white publication, and we like to play with that (by featuring monochrome videos and photography, for example), but we’ll happily consider your polychrome submission.

Submissions are ongoing throughout the year. We consider artists with both extensive and limited publishing experience. We accept simultaneous submissions but please inform us if your work has been accepted elsewhere.

There’s no need for an extensive cover letter or publication history but please tell us who you are, what kind of writing or art you do, and a bit about what you’re sending us. There are no formatting requirements for text submissions. There is no fee to submit. Please send submissions as email attachments whenever possible; multimedia submissions may be sent as links.

SORTES is edited by Jeremy Eric Tenenbaum and Kevin Travers. We live in Philadelphia but we invite writers and artists everywhere to read, contribute, and adore us.

Events

SORTES regularly offers readings and performances.

For upcoming events, please check here and our Facebook page.

Coming Up:

SORTES #6 Alive!

JUNE 25, 2021 at 7PM

YOU MUST JOIN US for this reading starring some or all of Issue 6's intense, inimitable readers, including Christian Bufo • Joshua Martin • Kailey Tedesco • Konstantinos Patrinos • Luke Condzal • Robert Wexelblatt • Shine Ballard • Stephanie V Sears • Victoria Mier • and/or Warren Longmire!

Your host -- tan, rested, and ready after his Issue 5 hosting sabbatical -- will be co-editor Kevin Travers.

The event is free, public, and compulsory.

Radio SORTES

See Events for upcoming Radio SORTES performances.

The 39 Steps, February 19, 2021

The Radio SORTES Players performed this classic adventure story, written by John Buchan and adapted by Jeremy Eric Tenenbaum from Hitchcock's 1935 film and the 1937 Lux Radio production. It starred Brenna Dinon • Heather Bowlan • Rosanna Byrnes • Betsy Herbert • Iris Johnston • Warren Longmire • Brian Maloney • Britny Brooks • Nicholas Perilli • Kelly Ralabate • Dwight Evan Young • Emily Zido • Victoria Mier • Jeremy Eric Tenenbaum • and Kevin Travers.

Halloween Eve Special, October 30, 2020

The Radio SORTES players presented a live Halloween Eve special: two programs of classic old time radio horrors. The shows -- including dialogues, music, and sound effects -- were performed for a live Zoom audience.

The Suspense episode “The House in Cypress Canyon” was originally broadcast December 5, 1946 and the Inner Sanctum Mysteries episode “Voice on the Wire” was originally broadcast November 29, 1944. Both programs were performed by Kevin Travers • Sean Finn • Britny Perilli • Don Deeley • Brian Maloney • Betsy Herbert • Kyle Brown Watson • Nicholas Perilli • Emma Pike • Kyle Brown Watson • Susan Clarke • Kyle Brown Watson • and Jeremy Eric Tenenbaum. Between episodes, we presented an original commercial in period style written and performed by Kevin Travers.

Introduction

Suspense, "The House in Cypress Canyon"

Commercial

Inner Sanctum Mysteries, "Voice on the Wire"